Article / interview

How (not) to write about disabilities in books for children and young people

For several years now I have been curious about the literary portrayals of people with disabilities in children's and young adults literature. What titles come to mind when we put these two terms together: disability and children's and young adults literature?

The Secret Garden by Frances Hodgson Burnett? Colin is in a wheelchair, but that is more likely the result of his illness and inadequate care by adults. Maybe Katarynka by Bolesław Prus? It is a moving novella, but over 140 years have passed since its creation, and in the meantime there have been colossal changes in children's development (and the time horizon they are able to assimilate) and in the scope of the possibilities and limitations of people with visual impairments. Also Spotkanie nad morzem by Jadwiga Korczakowska, written in the 1960s, no longer meets the conditions of relevance and accuracy, because the description of Elza's functioning contained in it perpetuates in the reader's erroneous opinions that the lack of sight prevents access to education and culture, condemns isolation and social rejection. The ending of the book also fits into the socially established belief that a blind person can feel happy only when they regain their sight.1

Does contemporary literature offer a more nuanced and, above all, non-stereotypical approach to visual impairment (and disability in general)? It is still not free from problematic images of disabled characters. An example is Tydzień Konstancji by Olga Masiuk (2008).2 This is a short, illustrated story in which the narrative about the titular girl is told according to the days of the week – each of them has its own unique character, perceived by the girl in a non-visual way: through smell, touch, hearing, and finally through the constant rhythm of everyday activities (and deviations from them).

The author tries to present the perception of the world by a blind child in an interesting way. She shows what great descriptive and cognitive power words can contain. However, in many places she creates an image that fits into a socially established stereotype. Since Konstancja is a child (about 10 years old), she naturally does not yet understand everything which is happening around her, and in addition, due to her visual impairment, she has fewer opportunities to learn, develop through observing others, therefore, she requires more support. Despite this, however, a certain naivety (gullibility) of the girl is surprising, as well as the fact that she quite often describes herself through the prism of deficiencies and limitations. It should be emphasized here that children with congenital disabilities have a different approach to their own disabilities than those who became disabled later, and they also perceive the world around them in a different way and assess their own abilities. They learn about their limitations in contacts with other people, hence the appropriate attitude of peers, family and many other people they come into contact with every day proves important. That is why the last scene in Olga Masiuk's book seems quite surprising. The girl's biggest dream is to ride a bike and feel the wind on her cheeks. What idea does her family come up with? They create a completely artificial situation in which Konstancja is seated on an exercise bike in a gym, and air from a hair dryer is blown onto her face. Even if we take into account the family's concern for the girl's safety, such a scene proves thoughtlessness and even a certain impudence towards a child with a visual impairment.

Here, an excellent opportunity to show the child reader that blind people can, in many cases, undertake the same activities as visually able-bodied people, only the form of their performance will be different, e.g. riding a tandem, going to the cinema to see a film with audio description, getting to school independently using a white cane, etc.

In this context, the problem of the author's inspirations and preparation for taking on the subject of disability reappears again. Masiuk writes about the circumstances in which the work was created:

"The book was inspired by a girl I met on Warsaw-Gdańsk train, who in my head and later in my story became Konstancja. I don't know her name, because I didn't dare to ask. In fact, I didn't say anything during this journey, which we made together and at the same time separately. The girl was visually impaired. I listened to her stories and tales. She spoke in an intriguing and rich language, as if she was filling images with words that she couldn't fully see. I was fascinated by it. This is how Konstancja was born".3

We see in this description curiosity, but also distance, an inspiring experience, but limited to silent observation, boldness in imagination and at the same time fear of real, physical contact. It is worth considering whether there are (and where, if there are) limits to invention in creating stories with the participation of characters with disabilities. On the one hand, such creative attempts, showing the diversity of the human world, are very valuable, on the other hand, authors often stop at the level of inspiration from real situations, creating the plot and characters according to their own discretion and their own intuition. They have the right to do so, but when taking on certain topics, they should be expected to show greater responsibility, a deeper sense of real problems and understanding the specificity of the people or social groups that they want to describe.4

Why is the attitude of authors towards the issue of disability, especially in their works for children and young people, so important? Because culture and media are one of the most important tools which can influence changes in social attitudes towards people with disabilities - both in adults and children. It is worth paying attention to research on the perception of people with disabilities by children. Of particular value is the publication by Anetta Soroka-Fedorczuk5, who conducted a series of interviews and surveys with several different groups of 6- and 10-year-old children together with their teachers and parents. The author subjected her respondents' answers to a detailed analysis, taking into account various possible factors that could influence the descriptions and assessments of people with disabilities made by children. These variables included: the frequency and quality of conversations conducted by teachers and guardians, age, gender, family experiences (one of the family members is a person with some disability) or the presence of a disabled child in the peer group. Summarizing her research, Soroka-Fedorczuk clearly points to the diversity of descriptive and evaluative statements resulting primarily from age and the totality of experiences already acquired (quantity and contacts with disabled people). She also writes (I will allow myself to quote a longer fragment):

"The image of disabled people in the opinions of six- and ten-year-old children indicates that children perceive disabled people in various places and situations, and therefore that these people emerge from isolation. This image is diverse in terms of description and assessment. It may be worrying that - in terms of the quality of information about disabled people - it is often fragmentary, full of fears, unreal, colloquial, shaped on the basis of fragmentary, incomplete information (in the form of stereotypes and prejudices) provided sporadically by various sources (parents, teachers and other people, mass media), as well as as a result of the child's observation of disabled people. The lack of contacts between able-bodied children and disabled people and professionally provided knowledge (e.g. during conversations about disabilities) and other experiences contributes to the creation of such an image. The conducted research confirms the thesis that children’s perception of disabled people (in the descriptive and evaluative aspects) is an expression of individual experience, i.e. the child’s multifaceted participation in learning about the world around them, in which disabled people are present, and that this process is influenced by cultural patterns and norms transmitted (consciously and unconsciously) by various sources of information in the broadly understood educational process".6

Although the statements of the minor respondents were varied, there were often comments indicating simplified and paternalistic ways of describing disabled people as weaker people who should be helped. Yes, many people with disabilities, including children, need additional support, but this fact should not overshadow the whole picture of a given person. And it often happens that the term disabled serves as the entire characteristic, which indicates a certain (not always conscious) closure to the possibility of getting to know each other better and establishing closer contacts.

On the other hand, it is easy to swing in the opposite direction, presenting people with disabilities in culture and media who achieve spectacular successes, which creates the risk of perpetuating two extreme images of people with disabilities: hero and victim, as Piotr Stanisławski7, among others, rightly points out. Intermediate situations are rarely shown, and such apply to most people with disabilities. Hence the need to present the widest possible spectrum of ways of functioning, personalities, interests and needs of people with disabilities. It is here, in addition to creating the most frequent interactions with people with disabilities in the social space, that the field opens up for various cultural works, including literature, to present young recipients with diverse images of people with disabilities. It is important that these different activities: conversations with adults, reading, film screenings, playing with a disabled peer, contacts with adults with disabilities, discussions among friends and acquaintances, complement each other. Limiting yourself to one type of activity or relying on others (e.g. reading a book instead of – and not alongside – a conversation with a parent or teacher) may not bring any positive effect at all.8

For a dozen or so years, the children's book market has been changing dynamically; it has grown significantly and dispersed (in terms of publishing houses). We are also dealing with a major qualitative change in terms of subject matter and aesthetic patterns. In addition to classic narrative, genre or illustration conventions, we can observe numerous more or less successful experiments that attempt not so much to educate or instill correct behavioral patterns (although they do that too), but to show the young recipient the diversity and complexity of the world around them. Above all, the attitude towards the child reader has changed - they are a fully-fledged, subjective individuals who have the right to ask questions and receive answers adapted to their cognitive abilities or inspiration for their own reflections and explorations. Such books are a challenge primarily for adults, because they require a slightly different attitude, as well as a readiness to answer the not always easy and convenient questions generated by reading. An excellent example of such an unconventional, seemingly cheerful, and in fact provoking numerous reflections and discussions between children and adults, is Mallko i tata Gusti'ego9 , presenting the evolution of the relationship between the author, artist and his son with Down syndrome. In 2016, this title was awarded the most famous award in the field of children's literature, the BolognaRagazzi Award in the new disability category. This fact reflects the increasingly strong tendency in world children's literature, consisting in introducing various difficult topics - and in a realistic convention, not fairy tale or symbolic - to children's books. Moreover, in the jury's verdict10, the disabled child as a reader (or, more broadly, a recipient of culture) was pointed out, as well as the importance of representing various social groups in literature, including people with disabilities. As Aniela Korzon, a researcher in the field of deaf education, writes, in order to arouse and develop the reading interests of hearing-impaired children (or those with other disabilities), it is worth offering them books whose plot concerns disabled children or adults, including the deaf.11 Literature that positively presents characters with hearing impairments, their ways of communicating, and has interesting content, can significantly contribute to raising the level of acceptance of one’s otherness and one’s own self-esteem, as well as to searching for more interesting books, and thus to the development of reading skills.

It is also worth remembering that the target group of recipients of children's and youth literature, although relatively small and specific, still has considerable diversity within it in terms of the level of interest in the subject (and its knowledge), the degree of mastery of the language, the stage of general cognitive and intellectual development. The perceptive abilities of a five-year-old are different, those of a nine-year-old, and still others of a child in teenage years. This is an important element, both at the stage of creation of a given work and later, in social circulation (reception by young readers, as well as adults, including critics and researchers).

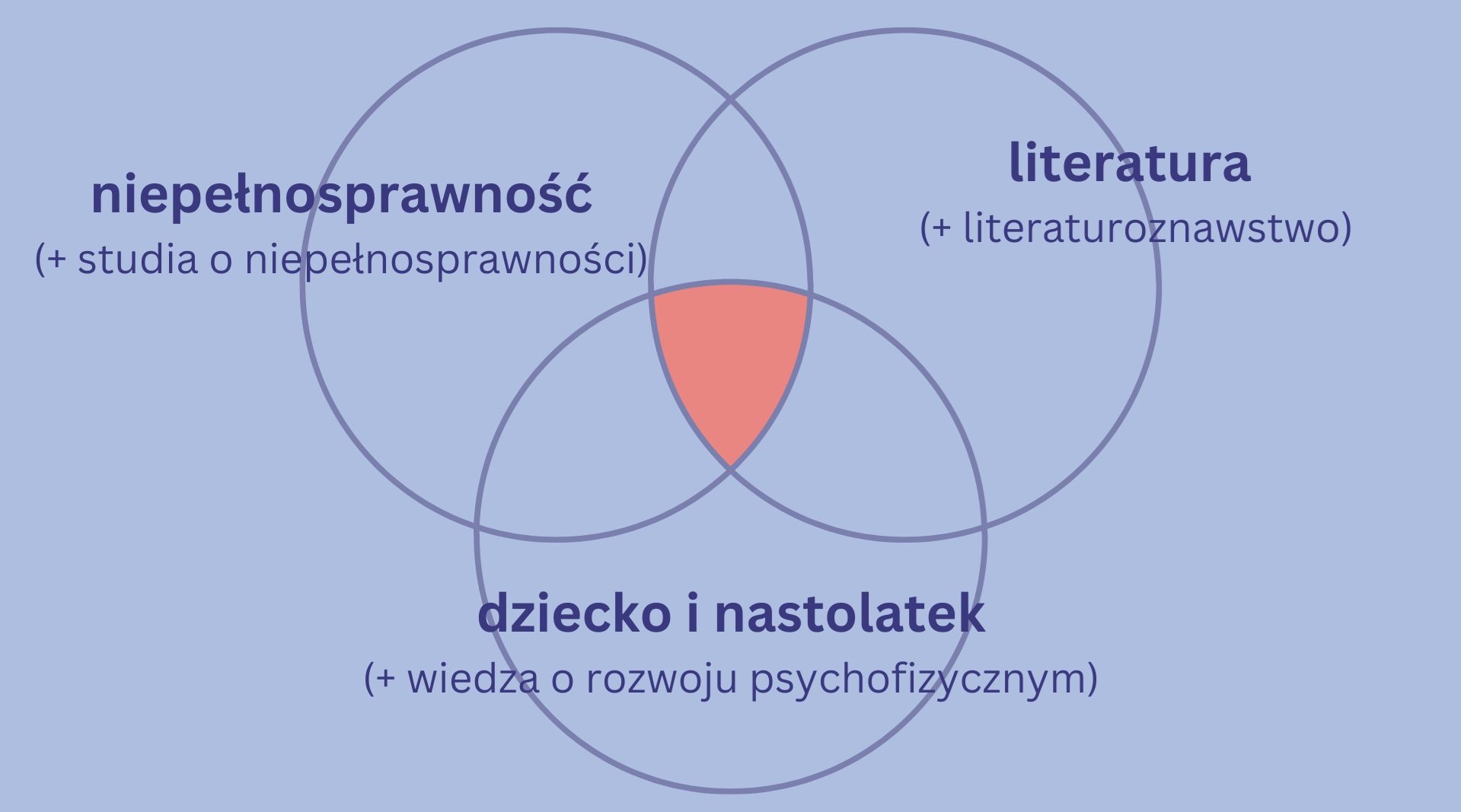

The above considerations concerning literary representations of characters with disabilities are part of the socio-cultural trend of disability studies, which undermines the previous dominance of the medical-functional perspective in discussions of issues related to disabilities. This new methodological approach of an interdisciplinary nature is the basis of disability studies, developed since the 1980s in the United States (later also in other countries).12 Disability studies, in the most general sense, is a critical reflection on disability, its history and social context. It views disability as a social, political and cultural phenomenon, and not as an exclusively medical phenomenon.13

According to Simi Linton, author of the foundational publication for disability studies, Claiming Disability. Knowledge and Identity (1998), issues such as the opposition of independence and dependency, aesthetic preferences present in a given culture, health and its definitions, the problem of ableism, i.e. irrational prejudice against disabled people (especially in its veiled forms) and its impact on the whole of social life should be subjected to critical reflection.14

In Poland, only for a few years now have scientific works in the perspective of disability studies appeared on a wider scale, mostly of a sociological and literary nature. They are - for now - scattered, introductory, fragmentary, but there is a great research potential, and - equally importantly - a social (and political) one. Due to their interdisciplinary nature, these studies draw on the achievements of various fields of science and inspire new directions of research. Above all, they have (or should have) strong connections with social reality: they can describe not only historical processes, but also analyze contemporary phenomena, social movements; moreover, they can also cause changes on a wider scale, influence social awareness (through education of pupils and students, various types of publications, participation in projects, cooperation with various entities and institutions, etc.).

By adopting the social perspective of disability, I have consciously refrained from citing here scientific definitions of this phenomenon, which in the vast majority still present a medical approach to disabled people and treat disability as a consequence of illness or injury and as a deviation from the physical norm, requiring appropriate treatment. Without ignoring the medical, health aspect of psycho-physical dysfunctions and the fact that adaptation to a new situation (after an accident, illness, etc.) requires a lot of effort and patience, it is worth - as Elizabeth Barnes, author of The Minority Body (2016) aptly notes - treating the category of disability neutrally, not judging it as bad or good. And above all, disability should be understood as a phenomenon only partly shaped by body features, and partly by the attitude of society towards people with physical disabilities.15

The cultural and social perspective of disability allows us to take a critical look at the ways in which disability is presented in cultural works, including literature for young adults, to identify stereotypical, superficial depictions of people with disabilities, to analyze the adequacy of the language used to describe these disabilities and the relationships between disabled characters and the world around them, and to point out the deliberate excessive emotional involvement of the recipient (evoking cheap thrills). Due to their recipients, a significant number of works for children about disabilities are problem books, i.e. books in which "both he [the disabled character] and the plot are subordinated to educational goals: explaining to children the nature of the disease, its symptoms, and shaping the right attitude towards children suffering from it".16 Although such an approach is necessary and valuable, one should approach the narrative strategies chosen in individual works critically, because some of them co-create accompaniment literature (so-called second fiddle books), which according to Krystyna Zabawa is characterized by the fact that a different, disabled character is introduced into the world presented as a kind of accompaniment for the main characters. Their sole purpose is to help them mature, grow into responsibility, transform from a self-centered, egotistically oriented child into a friend open to otherness, eager to help. This plot pattern is already so exploited that it requires considerable writing skills and a high level of empathy towards the characters to create a story that engages a young (especially adolescent) reader.

References:

1 Czerwińska Kornelia, Wizerunek osób niewidomych w literaturze dziecięcej - przełamywanie czy kształtowanie stereotypów?, „Wychowanie na co Dzień” 2014, nr 1 (244), s. 32. See also: Zabawa Krystyna, Ryzyko spotkania z Innym - niepełnosprawny we współczesnej literaturze dla dzieci, w: Edukacja polonistyczna wobec Innego, red. Anna Janus-Sitarz, Kraków 2014, 125-126.

2 Masiuk Olga, Książkę zainspirowała dziewczynka..., retreived: 30 V 2019, http://www.wydawnictwodwiesiostry.pl/katalog/prod-tydzien_konstancji.html.

3 Soroka-Fedorczuk Anetta, Osoby niepełnosprawne w opiniach dzieci, Kraków 2007.

4 Ibidem, 154-155.

5 Fidowicz Alicja, Językowy obraz osób niepełnosprawnych wśród uczniów klas VI szkoły podstawowej, w: „Przegląd Pedagogiczny” 2015, nr 2(13), s. 159 [online] [retrieved 16 VI 2018: https://repozytorium.ukw.edu.pl/handle/item/3677].

6 Stanisławski Piotr, Od ofiary do herosa [online] [retreived 16 VI 2018: http://www.niepelnosprawni.pl/ledge/x/7925].

7 I recommend a very interesting analysis of the discussion surrounding Malina Prześluga's drama Debil: Muca Klaudia, Opowiedzieć niepełnosprawność. Wybrane problemy kulturowych reprezentacji niepełnosprawności. Gdańsk 2024, 104-120.

8 Korzon Aniela, Literatura piękna w rehabilitacji niesłyszących, w: Świat pełen znaczeń - kultura i niepełnosprawność, ed. J. Baran, S. Olszewski, Kraków 2006, 268.

9 Zdanowska Marzena, Nie-złe upośledzenie, „Znak” 2017, nr 1(740), 8.

10 Ibidem, 112.

11 Gusti, Mallko i tata, Warszawa 2018.

12 BolognaRagazzi Award: The Winners of the 52nd Edition [online] [dostęp 20 V 2018: www.bolognachildrensbookfair.com/media/libro/press_release/2016/20160322/eng/11_BRAW.pdf].

13 Masiuk Olga, Tydzień Konstancji. Warszawa 2008.

14 Rembis Michael, Pamuła Natalia, Disability Studies: A View from the Humanities, „Człowiek - Niepełnosprawność - Społeczeństwo" 2016, nr 1(31), 6-7.

15 Fidowicz Alicja, Niepełnosprawność w polskiej literaturze dla dzieci XIX wieku, „Wielogłos. Pismo Wydziału Polonistyki UJ” 2016, nr 4(30), 112.

16 Zabawa Krystyna, op.cit., 127.

Information

ORCID: 0000-0003-1276-7156

Projekty badawcze:

-

Cyfrowa infrastruktura badawcza dla humanistyki i nauk o sztuce DARIAH-PL – w ramach Działania 4.2 Programu Operacyjnego Inteligentny Rozwój 2014-2020 (POIR), czas realizacji: 2021-2023, charakter udziału: wykonawca, wkład w tworzenie wartości niematerialnych i prawnych projektu, projekt afiliowany w: Poznańskie Centrum Superkomputerowo-Sieciowe afiliowane przy Instytucie Chemii Bioorganicznej PAN, kierownik grantu: Tomasz Parkoła.

-

Polonistyka wobec wyzwań współczesnego świata.

Stypendysta Ministerstwa Nauki i Szkolnictwa Wyższego ("Diamentowy grant"), laureat konkursu Fundacji na rzecz Nauki Polskiej ("Monografie"), Konkursu Polskich Krytyków Muzycznych, finalista Nagrody im. Andrzeja Krzyckiego i Nagrody Literackiej Prezydenta Miasta Białegostoku.

Autor monografii "Kruche jest piękne. Męskości w polskiej prozie emancypacyjnej po 1989 roku".

ORCID: 0000-0002-2318-9622

See also

Interview with Prof. Anna Frajlich, Senior Lecturer, Emerita of the Department of Slavic Languages at Columbia University

Professor Anna Frajlich, a renowned poet with impressive dossier of achievements, who left Poland in 1969 because of the anti-Semitic campaign, has lived in New York for years. Here, at the Slavic Studies Department of New York University, she defended her doctoral thesis on the legacy of ancient Rome in the Silver Age of Russian Poetry, and for 34 years, from 1982 to 2016, she was a lecturer at the Slavic Studies Department of Columbia University. Currently, retired for eight years, she continues to actively participate in American and Polish literary life, taking part in meetings, conferences, and talks. One of them was conducted by Przemysław Górecki in the New York apartment of the professor and her husband.

Priceless testimonies of landscape, or environmental literary history in practice

Klaudia Węgrzyn talks to Dr. Hab. Marta Tomczok, Professor at the University of Silesia.

Art in the Places of Death. An interview with Prof. Halina Taborska

"Halina Taborska's book (...) is a peculiar study of the aesthetics of an anti-humanistic act. In fact it introduces such "aesthetics" to the readers, and we are presented with a very carefully prepared documentation of various objects, material and spatial shapes, "installations", murals, museum organizations and documentary activities. These are various shapes in the public space which mediate our perception of an unimaginable crime or "blinding” shapes that protect us from the damages of seeing it again. By bringing this collection of practices together, the book shows their character and multiplicity. The research material gathered in the publication and the scholarly approach make it a must-read not only in the study of war crimes in Europe, but also in the study of symbolic representation of mass crimes - especially in the field of cultural studies, cultural anthropology and art history.” (Prof. Jan Stanisław Wojciechowski, Academy of Fine Arts in Warsaw - excerpt from the review on the cover).

A Rocker Professor

A graduate of Polish studies at the Faculty of Humanities of the University of Zielona Góra. Used to be a presenter at Radio Zielona Góra, and now she is a professor at the University of Zielona Góra as well as the head of the Journalism Laboratory and a member of the Polish Linguistic Society. Here come the many faces of Professor Magdalena Steciąg, Phd DSc.